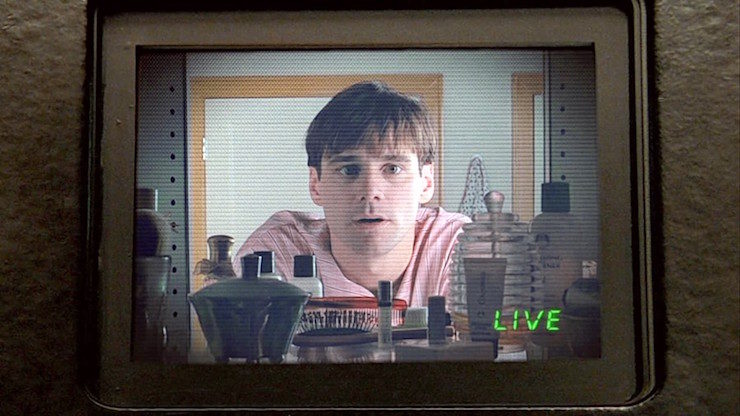

Truman Burbank is living the good life on idyllic Seahaven Island. Sure, his college sweetheart warned him that he was the target of a conspiracy, but she was having a nervous breakdown and soon moved away to Fiji. Now he’s thirty-years old with a good job, a beautiful wife, and friendly neighbors. How can he complain? Truman’s life is the American dream.

Of course, what Truman doesn’t realize is that Seahaven Island is a domed set, everyone he’s ever known are paid actors, and every moment of his entire life is the subject of the massively popular Truman Show. Megalomaniacal producer Christof pulls strings from behind the scenes, supplying actors with lines, fueling Truman’s fear of water and travel in order to prevent him from venturing off the island, and manufacturing interpersonal drama in Truman’s life to maximize the show’s ratings.

In real life, here in 2018, we are all the stars of our own personalized, algorithmic Truman Shows. Facebook titillates us with finely tuned updates. Google answers every conceivable question. Apple swaddles us in their impeccably-designed walled garden. Amazon anticipates our every whim. Netflix keeps us happily entertained. Uber and Lyft whisk us between Airbnbs with unparalleled efficiency and precision.

Truman, of course, eventually starts to notice odd discrepancies in the world around him: rain that falls only on him, a spotlight crashing from the sky, a radio channel that narrates his every move. Maybe he shouldn’t have dismissed his old sweetheart’s warning so easily. Suspicious, he begins to search for clues, forcing Christof to intervene with increasingly dramatic and implausible distractions. Truman surprises his wife by taking her on an unplanned road trip, but Christof doesn’t have adequate time to prepare and fabricates emergencies to block their path. This sparks an argument between Truman and his wife, and she breaks character, confirming the conspiracy. Seeking shelter from a world that no longer makes sense, Truman withdraws to sleep in his basement.

Today, it feels like our own deepest fears are coming true. Algorithms sequester us in filter bubbles and serve up increasingly polarizing morsels in a no-holds-barred battle for our attention, which they then auction to advertisers. Worse still, bad actors hijack these systems to contaminate our worldviews, spread propaganda, and influence our elections.

The future is cloudy with a chance of Black Mirror and we don’t know who to trust.

By constructing a digital Truman dome for each and every one of us, has the internet locked us in cultural solitary confinement? Has isolation robbed us of the ability to see the forest for the trees? If reading the headlines is an exercise in navigating layers of existential deception like the denizens of Westworld, can we even trust ourselves? These are the kinds of questions that I explore in my own science fiction novel, Bandwidth, which extrapolates hackers hijacking the global feed to fine-tune the psychology of world leaders.

One night, Christof notices that Truman is somehow sleeping off-camera. He orders an immediate investigation and discovers that Truman has left a dummy in his place. The entire time that Truman appeared to be sleeping downstairs, he had been secretly digging an escape tunnel. The basement wasn’t a hideaway, but the unlikely birthplace of a bid for freedom.

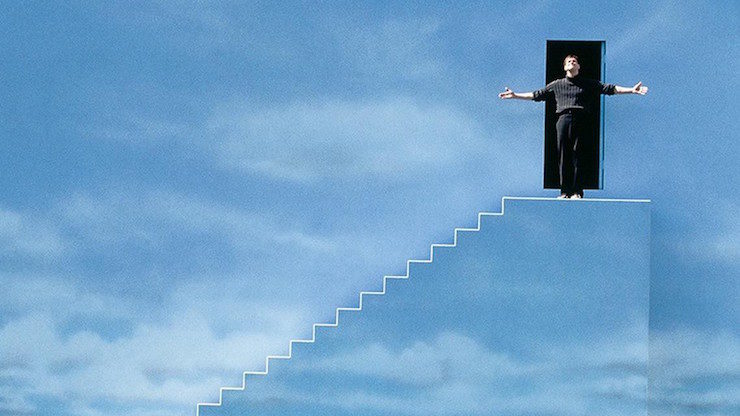

After a frenzied search, Christof finally locates Truman. He has commandeered a small boat, overcome his engineered fear of travel and drowning, and is sailing away from Seahaven Island. Determined to avert the star’s escape and keep the show going, Christof unleashes a manmade lightning storm. But when it becomes clear that Truman would rather die than turn back, the producer finally relents and Truman nudges his prow through the edge of the dome.

As Truman looks around at the machinery that has determined every detail of his entire life, Christof makes one final appeal. The outside world is as artificial as anything you’ve experienced, he avows. Return to the dome and you’ll live the rest of your life in comfort. Truman refuses and steps out into true sunlight for the very first time.

Cue credits.

If only it were so easy. As Orson Welles once observed, “If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.” Truman’s journey ends there, but ours doesn’t.

When trust is betrayed, the natural reaction is to disengage. We take social media vacations. We stop reading the news. We go off-grid. This psychological distance gives us the space we need to lick our wounds and regain our strength.

Buy the Book

The City in the Middle of the Night

But the internet has become essential infrastructure, the repository of all knowledge and the fascia that stitches together modern civilization. Cars are computers we drive in. Houses are computers we live in. Phones are computers we can’t live without.

We do not have the luxury of refusing Christof’s offer. The algorithms that shape our lives are too useful to lay down. They answer our questions, connect us to loved ones, guide us to destinations, improve medical care, and filter the digital infinite into the relevant finite. They are miracles that we take for granted; real-life magic. We cannot give them up.

Has technology trapped us between utility and manipulation? Is this a new kind of 21st century purgatory? As we emerge from our digital domes and blink in the too-bright sunlight, we might begin to notice something odd. Our physical lives are actually more ideologically segregated than we think. Our friends, family, and neighbors constitute a much more powerful filter bubble than our social media feeds. On the internet, dissenting opinions are only a click away. In the physical world, when was the last time a San Francisco software engineer flew to a Rust Belt town to strike up a political discussion with a disenfranchised local, or vice versa? In the current news environment, it might sound strange, but researchers Jesse Shapiro and Matthew Gentzkow confirmed this finding in a fascinating University of Chicago study on ideological segregation, concluding “We find no evidence that the internet is becoming more segregated over time.”

It turns out that we’ve been living under domes all along. Escape is not an option.

Instead, we must make our domes transparent, so we can assess for ourselves the methods and fairness of their inner workings. That means demanding better user visibility and control over the data that platforms collect. It also means challenging ourselves to venture beyond our too-often homogenous personal networks to meet new and different people.

We must pay for accountability so that the Christofs of the internet do not peddle the influence they wield to third parties, and we must recognize the tradeoffs when we pay in attention instead of dollars. That means supporting artists, journalists, activists, and platforms through patronage, subscriptions, and donations. It also means fact-checking that funny-because-it’s-true anecdote your friend told you at happy hour before passing it along.

We must build our own domes. That means using every resource at our disposal to create new technologies, platforms, communities, laws, and institutions that give users and citizens agency over their destinies, digital or otherwise. Moreover, it means pushing ourselves to learn more about topics foreign to us and choosing to wrestle with tough questions instead of accepting easy answers.

The movie leaves Truman’s off-camera future to our imagination, but I like to think that the college sweethearts are finally reunited. Maybe they leverage their celebrity to become leading civil rights activists, or perhaps they open a croissant bakery in Silver Lake and spend years in therapy. Regardless of the particular path they take, like Truman and Sylvia, we must find new ways to trust each other. The endings of our own shows depend on it.

Eliot Peper is a critically-acclaimed novelist and the author of Bandwidth, Borderless, Cumulus, Neon Fever Dream, True Blue, and the Uncommon Series. He lives in Oakland and maintains a popular reading recommendation newsletter.

This, a thousand times, every word. Especially the part about blaming the internet for the Dome. If anything the Internet exposes the Dome, and allows us a path to escape. The fact is, we are uncomfortable with what the Internet reveals to be outside of our Domes, and most of us double down on remaining within the confines of the world that has been created for us.